- Milan Castle

- Museums Libraries Archives

- Museo Pietà Rondanini - Michelangelo

- Museo d'Arte Antica

- Sala delle Asse - Leonardo da Vinci

- Pinacoteca

- Museo dei Mobili e delle Sculture Lignee

- Museo delle Arti Decorative

- Museo degli Strumenti Musicali

- Museo Archeologico - Sezione Preistoria e Protostoria

- Museo Archeologico - Sezione Egizia

- Raccolta delle Stampe "Achille Bertarelli"

- Gabinetto dei Disegni

- Archivio Fotografico

- Archivio Storico Civico e Biblioteca Trivulziana

- Biblioteca d'Arte

- Biblioteca Archeologica e Numismatica

- Casva (Centro di Alti Studi sulle Arti Visive)

- Ente Raccolta Vinciana

- Gabinetto Numismatico e Medagliere

- Opere dei musei in movimento

- The Castle and Milan

- Media gallery

- Plan your own tour

The Exhibition

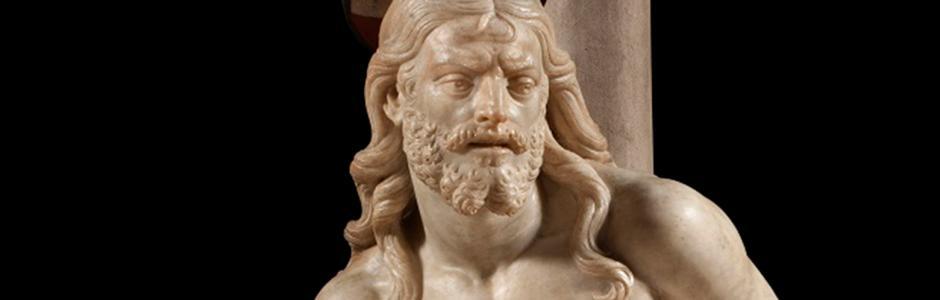

Body and Soul, from Donatello to Michelangelo. Italian Renaissance Sculpture

Curators: Marc Bormand (Paris, Louvre Museum, curator of the Louvre sculpture department), Beatrice Paolozzi Strozzi, director of the Bargello Museum from 2001 to 2014; and Francesca Tasso, curator in charge of the Artistic Collections of Castello Sforzesco in Milan.

Exhibition video preview

The exhibition, in collaboration with the Louvre Museum, is dedicated to Italian Renaissance sculpture, from Donatello to Michelangelo (1460-1520 circa). The exhibition aims to use sculpture which dialogues with paintings, drawings, and other objets; art to highlight the main themes running through Italian Renaissance art in the second half of the 15th century, and reaching its peak with Michelangelo, one of the greatest creators in the history of art. A new interest in the human figure, which is no longer detached from feelings but deeply linked to the soul, is one of the many innovations brought by Renaissance. According to the innovative interpretation given by the sculptors of this time, the motions of the soul are made visible through the attitudes of the bodies. Divided into four sections with over 120 works on display from the world's most important museums, the exhibition follows the same path as the one at the Louvre, except for the last room: while the Slaves (or Prisoners) were exhibited in Paris, in Milan the last room will be showing the Rondanini Pieta. Both immovable works by Michelangelo.

1. Looking at the ancients: Fury and Grace

Fury and grace make up the first major theme of the exhibition. The interest in complex compositions and exaggerated body movements becomes prevalent in many sculptors and will be documented through the works by Antonio del Pollaiolo, Francesco di Giorgio Martini or Bertoldo, up to Verrocchio, Leonardo, and Gianfrancesco Rustici. The complexity of muscular strength, the twisting of the male body, as well as the expressive effects of the most intense passions of the soul are brought into play. On the other hand, elegant draperies allow artists to reveal the charm of the human figure. Its lightness is enhanced by the movement of clothes and veils, through a practice of unveiling that ends up representing grace through both female and male nudes.

2. Sacred art: Affect and Persuasiveness

Affect and persuasiveness became the two key words in religious sculpture: following the work by Donatello around 1450, emotion and the motions of the soul took centre stage in artistic practices, in the desire to deeply, even violently, affect viewers. It is therefore a true theatre of feelings that unfolds in northern Italy between 1450 and 1520, particularly in the Deposition of Christ groups, such as those by Guido Mazzoni in Emilia and Giovanni Angelo del Maino in Lombardy. This search for religious pathos is also embodied in the moving figures of Mary Magdalene or Saint Jerome that flourished in Italy during this

period.

3. From Dionysus to Apollo

Between the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th century, a tireless reflection on classical antiquity was expressed in works based on the great classical models such as the Laocoön or “Spinario”, moving between the two Apollonian and Dionysian extremes. Concurrently with painting – see the gentle style of Perugino or the young Raphael –, sculpture conducted a search for a new harmony that would transcend the naturalism of extreme gestures and feelings. While this search for expressive beauty was particularly evident in Veneto and Lombardy – with Riccio, Antico, Moderno, Cristoforo Solari, Antonio Lombardo, up to Bambaia – it was also actively conducted in +Tuscany by Jacopo Sansovino, Baccio da Montelupo, and Andrea della Robbia.

4. Rome “Caput mundi”

From the end of the century, we are back in Rome again, Caput mundi. Here, Michelangelo was trying to reach a formal synthesis where scientific knowledge of the body was to be complemented with an absolute ideal of beauty, and a desire to outperform nature with art. His search is told along a path that goes from the youthful classicism of “Cupid”, through the gigantic size of the “Slaves” (or “Prisoners”, on display at the Louvre) up to the ineffable and sublime nature of Rondanini Pieta, which may be admired (only) in Milan.